On a recent assignment for Avenues Magazine I had the pleasure of working with American photographer Brian Harmon. Although he has only lived in this country for a few years, Brian has managed to capture some extraordinary images of New Zealand. He's a photographer who is absolutely packed to the brim with talent and ability. Unfortunately, he is also a photographer who likes to get up early in the morning.

Brian: I was thinking of starting quite early.

Me: Ten o'clock?

Brian: I was thinking more like five.

We were spending a day with one of the last commercial fishermen on Lake Ellesmere. I tried to imagine five o'clock at the lake on a winter morning. It seemed inconceivable that anyone would want to subject themselves to such horror.

As I scraped ice from my car's windscreen at half-past five the next morning, I cursed Brian and his entire profession. We had compromised on seven o'clock: which still required me to leave my house at an ungodly hour. And yet somehow -- as I drove through an empty and slumbering Christchurch, and into the pre-dawn countryside -- I began to see that Brian might have a point.

It was good to be awake, and to be getting the most out of the day. In fact, I began to pity my fellow citizens lying in their beds. They were snoozing their lives away -- whereas I was making each minute count. I resolved to rise this early every morning from now on. I would seek new employment at a worthy organization. I would donate half of my income to sick children. I drifted into a reverie as I contemplated how beautiful my life would become.

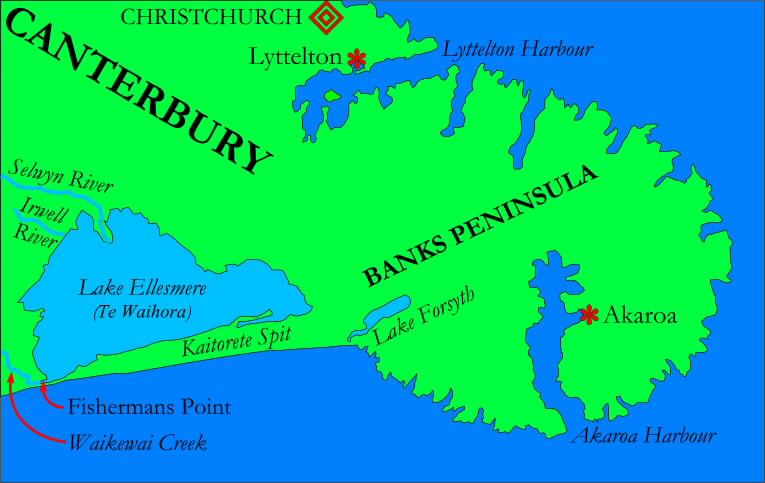

My car sped into the darkness: past the lights of Lincoln University; through the townships of Springston, Doyleston, and Leeston; and finally into Southbridge. After Southbridge I turned off the main road, and bumped along a gravel track to the village of Fisherman's Point. The peak of Mount Herbert was turning pink in the distance. Lake Ellesmere lay before me like a gigantic black tablecloth.

Brian's car was parked beside the lakeshore. "Decided I might as well get here at five anyway," he said. "I've got some nice shots of the dawn." He was bristling with cameras and enthusiasm. "Can't wait to get out on that lake and shoot some more film," he added.

His cheerfulness was already exhausting me. I felt an overwhelming urge to go home and return to bed. But in Fisherman's Point village, people were beginning to wake up. A light was switched on in a kitchen window. Smoke began to puff from one of the chimneys. Brian and I wandered down the main street. Our friendly fisherman, Clem Smith, lived in the last cottage before the harbour.

Clem was loading fuel cans into his ute. He was obviously a man who didn't believe in wasting words. "Gidday," he said. "We've got to drop by Malcolm's place, and pick up some long-fin eels for release."

Malcolm's hut was a only few hundred metres down the road. In his backyard, a row of deceased eels were waving stiffly in the breeze -- strung out on a whata to dry. Half-a-dozen live eels were writhing uneasily in a barrel beside the hut. Clem explained that low lake levels over recent years have meant that eels can't return to the sea by themselves. The lake fishermen must release some of their catch into the ocean, so that the eels can breed and maintain the population in Ellesmere.

It was a short drive to the sea. Malcolm's grand-nephew Taura helped Clem to empty the barrel out onto the beach. Clem's dog went barking mad at the eels, and Brian's camera clicked like a Geiger counter as he recorded their slithering journey into the waves.

Back at Lake Ellesmere the fishing boat was ready to go. I climbed aboard and immediately fell over -- hitting my head painfully on the fish hold. This seemed to give everyone a good laugh. To my surprise, Clem's boat was something of a speed machine, skimming along the surface of the lake at a tremendous rate, and amplifying the wind-chill to Antarctic proportions. Even Brian looked slightly chastened by the icy breeze.

We stopped at the first net, and Clem and Taura lowered themselves over the side of the boat. I winced with sympathetic hypothermia as they waded waist-deep through the wintry lake water. They lifted the net -- heavy and swollen with eels -- and Malcolm grunted with exertion as he hoisted it into the fish hold.

Clem, Malcolm, and Taura are the inheritors of a 150-year tradition of commercial fishing on the lake. In the late 1800s, at the height of the Ellesmere fishing industry, more than a hundred commercial fisherman worked here. In those days Ellesmere was the fourth-largest lake in New Zealand. Since then a third of the lake has been drained, and Ellesmere has dropped down the rankings to fifth-largest.

Nowadays the lake's area is just under 200 square kilometres. But when viewed from the swaying deck of a fishing boat it still looks unbelievably vast. It seems inconceivable that such a large body of water could be on the verge of environmental collapse.

Unfortunately, however, Lake Ellesmere's failing health is well documented. An Environment Court judge recently declared it to be eutrophic -- so polluted by nitrogen and phosphate compounds that algal growth has become over-stimulated. This is a hazardous state for a lake ecosystem. As the rampant algal growth decomposes it causes a reduction in the dissolved oxygen content of the lake water. Oxygen levels may eventually become so low that fish life will be unable to survive.

The eutrophication of Lake Ellesmere is the result of three main factors. Firstly, Ellesmere's 2,700 square kilometre catchment area produces a large inflow of fertilizer, animal waste, and industrial run-off. Secondly, the filtering wetlands which previously surrounded the lake have been largely destroyed. And thirdly, the lowland streams which feed into Ellesmere have been severely reduced in flow.

This last factor may be the final nail in the coffin. The reduced stream inflows are thought to be caused by excessive water extraction from aquifers in the countryside surrounding Ellesmere. As the stream inflows diminish, the pollutants in the lake become more concentrated, and the rate of eutrophication increases. With the rapid conversion of the Canterbury plains to dairying there is no expectation that the extraction of water will be reduced. In fact, it is anticipated that vastly increased amounts will need to be pumped from the ground.

All of this suggests a grim future for the lake. And it seems extraordinary that Ellesmere -- one of Canterbury's iconic landmarks -- might deteriorate into a large muddy puddle without any real public awareness of our loss. I had spent a fascinating day on the lake with Clem, but as I drove home I wondered if Ellesmere's precarious future might not be a better subject for an article. By a happy co-incidence, Jon Gadsby (the editor of Avenues magazine) agreed with me, and cheerfully accepted an environmental piece about a lake in lieu of a human-interest story on fishermen.

A few weeks after the article was published I had an interesting conversation. An acquaintance suggested that I had been too idealistic in my analysis. "Humans are part of the ecosystem as well," he pointed out. "We can't stop living our lives just because Ellesmere is in trouble. Lakes only have a finite existence -- and you should just accept that Ellesmere is finished. The sensible approach is to drain as much of the lake as possible, and turn it into pasture. Two hundred square kilometres would make a lot of dairy farms."

I would certainly agree that humans are part of the ecosystem, and I am pragmatic enough to accept the significant impact that we must make on the environment. But the loss of Lake Ellesmere is a heavy price to bear. If we give up on our fifth largest lake -- a piece of landscape big enough to be easily visible from space -- then where do we stop?

Since writing the article on Ellesmere I've kept sporadically in touch with Clem Smith. It transpires that his economy in spoken language is counteracted by an abundance of written prose. He is the author of numerous short stories -- beautifully-crafted observations on the human condition -- ranging from descriptions of office romances to affectionate portrayals of family life. It is extraordinary work, particularly from the pen of a bachelor fisherman.

On cold Canterbury days -- when the southerly rolls in and the rain hammers down -- I often imagine Clem out on the lake planning his stories. I'd like to think that in twenty years time Lake Ellesmere will still be there, and Clem too. Lifting his eel nets, and contemplating the human condition.

More on Lake Ellesmere:

- Brian Harmon has generously made a selection of his Ellesmere photographs available online.

- Avenues magazine have kindly allowed online access to my original article which provides much more detailed information on Ellesmere.

- The Waihora Ellesmere Trust (WET) has recently been formed with the aim of improving the health and biodiversity of Lake Ellesmere. Their website can be found here.

All images used in this post © Brian Harmon, 2006.