When I look back, I realize that my university career ended -- or, at least, began to end -- with a party.

I hadn't wanted to go, of course. But the Dean of Science, Gavin Ramsay, persuaded me that it would be good for my research. "Everyone needs a break now and then," he insisted. "I'm worried about you -- locked away in that laboratory all the time. You'll work ten times better after a night out."

Gavin was several years my junior -- a fact that, I admit, always rankled with me -- and he seemed determined to rub my nose in his youthful lifestyle. His house-warming party was every bit as awful as I'd anticipated: drunken students, loud music, no possibility of intelligent conversation. The only point of interest was one of the young women attendees.

Her name, I discovered, was Marianne. Not, I hasten to add, that I was interested in her from a romantic perspective -- she was far too dolled-up for my tastes -- but I was fascinated by the reaction she engendered in some of the other men who were present.

They reminded me of nothing so much as male insects responding to pheromones from a female. Men clustered all around her, preening themselves, making little jokes -- a veritable human mating-dance. Not a successful one, however. Marianne was clearly unimpressed by her suitors.

Later in the evening, when the music had been turned down, I found myself standing at the drinks table beside her. It seemed courteous to introduce myself. "I work with Gavin Ramsay," I said.

She looked instantly bored. "Not another scientist?"

"I'm afraid so. How about you?"

"I work in radio." She scanned the room for a more interesting conversational prospect, then finding none, asked: "What type of science?"

"Entomology. My research is mainly on Hemideina ricta -- the Bank's Peninsula tree weta."

Marianne walked away. There was no "goodbye", no attempt at even the flimsiest of excuses -- she simply left without a word. As an act of impoliteness it was absolutely breathtaking. A few seconds later, I saw her strike up a conversation with a young man in a leather jacket.

I felt a hand on my shoulder. "Hard luck," said Gavin Ramsay. "Still, at least you had a go."

"I wasn't having a go," I spluttered. "I was simply being polite."

"Sure," he replied soothingly. "Well, at any rate, I don't think she's much of a loss. A bit of a head-case, I've heard."

I spent the rest of the weekend in my laboratory. On Monday, I delivered my ENT302 lecture as usual. Walking back to my office, I noticed a young woman waiting in the corridor. It was Marianne.

My first reaction was to pretend that I hadn't seen her. But -- as I opened my office door -- she placed a hand on my arm, and asked, "May I talk to you? I'd like to apologize for my rudeness on Saturday."

It's hard to resist contrition -- particularly, I admit, from an attractive young woman. "You'd better come in then, I suppose."

I sat down at my office desk; Marianne perched on one of the chairs normally used by my postgraduate students.

"My behaviour was unforgivable," she said. "I can only excuse myself by explaining that I have a horror of insects. When you mentioned wetas -- I just had to get away, immediately. I'm so sorry."

In my profession, of course, I'd encountered entomophobia on a regular basis. "Don't worry," I told her. "I'd almost forgotten what happened until I saw you again."

"Thank you," she said. "You're very understanding."

There was an awkward silence. Then I asked: "Have you always been afraid of insects?"

"All my life." Marianne gazed out of the window for a few moments. "Actually, there is something else I wanted to ask you. I mentioned my job to you, didn't I?"

"You're on the radio."

"Oh, nothing so grand -- sorry if I gave that impression. I'm a receptionist at a radio station. It's the station that 'Gazza' works for, actually."

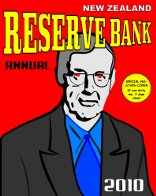

Gazza was a talk-back host whose fame -- or infamy -- had reached even my inattentive ears. "Isn't he the guy who compared the anti-smacking law to the Holocaust?"

"Yes, and the odd thing is that he says the same things off-air as he does on the radio."

"You mean that he genuinely believes what he says?"

"More than that. It's all he can say. Just those few bullet points that he repeats endlessly during his shows. He's like those toy dolls -- where you pull the string and get one of half-a-dozen random recordings."

Marianne rubbed her wrists nervously. "I had a very strange encounter with him last week. There was a fly in my office, but I couldn't find any fly-spray in the storeroom. So I picked up a can from the corner shop while I was out at lunch.

"I was just getting ready to spray the office when Gazza walked in. He jumped at me -- that's the only way I can describe it. He moved unbelievably quickly. The next thing I knew he'd grabbed my arms, and he was shouting: 'Women on the DPB should be sterilized!'

"He squeezed my wrists until I dropped the fly-spray. Then he picked up the can with a tissue, and hurled it out the window. All this time he was still shouting about the DPB. Everyone at the station came to see what the fuss was about -- afterwards they told me that he didn't like insecticide, and wouldn't allow it in the building."

I couldn't entirely see where Marianne was going with her anecdote. "Yes, that does seem rather over-the-top," I said hesitantly. "Although, of course, some people have funny ideas about pyrethrins."

"The thing is," Marianne continued, "I've been tormented by a crazy idea ever since. So crazy that I know you'll think I'm mad. I've got it into my head that Gazza might be, well, some sort of insect himself."

She gave a brittle laugh. "A highly-evolved one, of course. I've been reading about evolution -- mimicry is very common in the insect world, isn't it? Don't you think a species of insect might have evolved that mimics humans? They'd only need enough brain to say a few simple sentences, and then no-one would suspect a thing."

It took me a moment to digest what Marianne was saying. "Yes," I said finally. "That does sound a bit mad to me, I'm afraid."

Marianne coloured. "Oh, so you think I'm hysterical or something?"

"No, not at all," I reassured her. "It's an intriguing hypothesis, and I commend you on your ingenuity. But from a biological point of view it wouldn't make sense. For a start, that kind of adaptation would take hundreds of thousands -- maybe millions -- of years. And then what would be the evolutionary driver? What advantages would it confer on the insect?"

"Well, the insect would be scavenging from us and living off our scraps," said Marianne. "And they might have evolved alongside us, ever since we came down from the trees. Look at tramps and homeless people and so on: has anyone ever tested them to see if they're really human?"

I hardly knew how to reply to this. In all honesty, it seemed to me that she needed a psychologist more than an entomologist.

Marianne removed a snap-lock bag from her coat pocket, and held it out to me. "I've brought you a sample," she said. "Gazza wears his hair in a sort of horrible lank ponytail -- I found a few strands on the back of his chair."

I inspected the contents of the bag. The hairs were about 400 millimetres long; far too large to be insect in origin.

"Tell me you'll at least look at them," she pleaded.

* * *

"I give in. What are they?"

Mike Flaws was the department's microscopist. He'd called me on my office telephone; I could hear the excitement in his voice.

"What do you think they are?" I asked.

"On first inspection, I thought mammalian hair. But under an optical microscope they're obviously chitin -- so that means an arthropod. Then I looked under the electron microscope, and I could see that they're insect antennae. Bloody long ones."

I was shaken; an insect origin seemed impossible to me. "Any idea of species?"

"I've checked them against likely candidates, and I'm guessing some sort of cockroach. But I'll tell you what -- I wouldn't want to meet the bug that these came from. You wouldn't be stepping on it; it'd be stepping on you."

I put down the phone. My initial assumption had been that Marianne was a fantasist. Now I knew that she must be attempting a hoax. But for what reason? And why would anyone go to this much trouble -- obtaining giant insect antennae from who knows where -- in order to trick me?

There were several possibilities. One of my colleagues could be playing a prank -- but that seemed unlikely; it was the sort of foolishness that would land them in front of a disciplinary committee. What about the radio station -- some sort of advertising gimmick? If so, what could it be? I wasn't famous, and they'd hardly sell advertising off the back of making me look gullible.

Could it be down to Marianne alone -- was she simply one of those dazzlingly pretty girls who get their kicks from hoaxing junior academics? The question answered itself: it was all too unlikely.

Eventually, after much deliberation, I resolved to take the battle to them -- whoever 'them' was. The

Gazza Show played on Radio Jive, and the telephone directory gave their street address as Jervois Road.

* * *

Marianne sat at the reception desk. I hadn't expected that. According to my plan, I would discover that she didn't work for Radio Jive at all -- thus exposing her story as an obvious fabrication.

She smiled when she saw me. "The hairs were from an insect, weren't they?"

"Yes."

"I knew it."

I'd forgotten how genuine Marianne seemed. If she was acting, she deserved an Oscar.

She leaned forward across her desk, glancing down the corridor. "We need to discuss this," she whispered. "There's a Belgian café just across the road. I'll meet you there when I finish work -- five o'clock."

A voice behind me said: "National productivity is low for no other reason that the laziness of our workers."

Gazza had emerged from the studio. He was staring pointedly at Marianne. Then he swivelled his head, and peered closely into my face. "The problem with this government is that it's full of teachers and university lecturers."

It wasn't difficult to understand how Marianne had arrived at her theory. Gazza's skin had a chitinous sheen; he moved in precise, almost invertebrate motions. The long hair was obviously that of Marianne's sample: thick and whip-like. His jaws twitched to reveal broad, closely-set teeth.

I found myself studying him as I would an insect. Yes, that hair could be modified antennae; the teeth would be calcium carbonate, of course. I glanced at his chest, he seemed to be breathing. That could be explained by abdominal contractions, moving the air in and out of his spiracles. It would be surprisingly easy to believe Marianne's theory.

Gazza's head flicked round to focus on Marianne again. "National productivity is low for no other reason that the laziness of our workers," he repeated insistently.

She lowered her eyes. "I'd better get back to work

then."

At five o'clock, I was waiting for Marianne in the Belgian café. It had been a strange afternoon. I still regarded her ideas as fanciful, of course -- and yet there appeared to be supporting evidence from Gazza's hair sample, and indeed from the physical appearance of Gazza himself. I wondered if I were losing my mind.

Six o'clock passed. Then seven, then eight. The café closed at nine o'clock. Marianne did not arrive.

I drove home and collapsed into bed. Nothing today made any sense.

At 1.00 am the phone rang. A woman was weeping on the other end of the line.

"Marianne?"

There was indistinct sobbing, then words: "Something terrible has happened."

"What's happened, Marianne?"

She was still sobbing. "I went into Gazza's office after work. Then -- I don't know -- something made me do it, I couldn't help myself."

"What did you do?"

"We had sex -- Gazza and I had sex."

"Did he force you?"

She could barely get the words out. "No, I wanted to -- I can't explain it -- I couldn't stop. And then when I came home I suddenly realized what I'd done. Oh God, suppose I'm pregnant to him -- a giant insect."

"Listen Marianne, pregnancy is impossible." I tried to remain calm. "Insects are in a completely different taxonomic phylum. It must have been pheromones -- that's the obvious explanation -- and it makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. It's as if he drugged you, Marianne. It's not your fault."

She broke into weeping: "Can you come to see me? Please?"

"Of course -- I'll come straight away. What's your address?"

It was fortunate that I didn't pass any police cars that night. My speedometer touched 120 along Newton Road. I expected to find Marianne hysterical, screaming, possibly

even suicidal. It never occurred to me that she would be calm.

She took her time in opening the door to my agitated knocking. "Oh, you came? You needn't have -- I'm perfectly alright."

I was confused: "But what about everything you told me on the phone?"

"Oh yes, I'm sorry if I sounded upset -- but I've thought about it now and I'm quite happy. It's lovely to be pregnant. I'm really looking forward to having Gazza's babies. It will be wonderful."

A ripple of shock surged through my body. "Marianne, I know exactly why you're so calm, but you shouldn't be. It's the eggs -- they're releasing chemicals to tranquillize you. It's a mechanism used by parasitic insects."

"My beautiful babies," said Marianne idly.

"They're not your babies, Marianne. They're Gazza's -- and the other insect that Gazza must have already mated with. You weren't having sex, Marianne. Gazza is female. She was using her ovipositor to lay eggs inside you."

"But they'll be my own beautiful babies when they're born, won't they?"

I grabbed her by the shoulders. "Listen to me, Marianne. They won't be born -- they'll hatch inside you. And then..." I found myself struggling for the right words, "and then they'll start... eating. We need to get you to hospital right now, Marianne."

She gave a slow, radiant smile. "But can't you see how glorious it is to participate in the birth of a new world? To give my body to nourish a truly efficient society -- one without political correctness or nanny-state interference?" She glanced over my shoulder. "You think so, don't you darling?"

Gazza seized me from behind. His voice rasped in my ear: "The problem with the justice system in this country is too many do-gooders -- we must bring back

the death penalty!"

I fumbled for the fly-spray in my pocket. Gazza glimpsed the can; threw me across the room. Glass shattered. I fell onto a carport roof, tumbled off to land on a concrete path. I could see Gazza silhouetted in the broken window. She opened her jaws and hissed.

The fly-spray was lost; so were my car-keys. At the corner of the street a Night 'n' Day had its lights showing. Gazza leapt from the window-sill. I hurdled over the gate, slipped and fell, righted myself and sprinted towards the shop.

"Hello, dear." An elderly Indian lady was knitting behind the counter.

"Fly-spray?"

"Third aisle, dear."

I grabbed a pair of cans, flipped off the lids. "Sorry, I'll have to pay for these later."

My fingers were on the spray-buttons; I peered cautiously out of the shop-door.

And that was when the building fell on me.

* * *

Actually, it wasn't the building. It was the Indian lady with her grandson's cricket bat. The Herald's crime section ran a headline the next morning: "It's a Six! Shoplifter Laid Low By Cricket-Playing Grandma."

By that stage, I had regained consciousness. It wasn't a pleasant awakening -- the police had me handcuffed into a hospital bed. My subsequent decision to tell them the-whole-truth-and-nothing-but-the-truth wasn't exactly the most sensible thing I've ever done. It provided The Herald with another good headline: " Shoplifting Entomologist Explains: 'I Fought Giant Bug'."

Twenty-four hours later, I was officially finished as a scientist. My colleagues had abandoned me; one of them gave an off-the-record interview claiming that I'd always been mentally unstable. My only consolation was that the newspapers soon lost interest -- and my court-hearing barely made The Herald's back pages. I don't suppose many people even read it: "Judge Swats Bug Doctor: Sentenced to Psychiatric Care."

Since my release, I've tried every possible approach in finding Marianne -- even to the extent of cashing in my superannuation account to hire private detectives. But I've discovered no trace of her; and now I can only hope that she didn't suffer.

Of course, there's been no problem in keeping track of Gazza's activities. He's more popular than ever on the radio -- and the latest news is that he's planning to run for city mayor. They say journalists love the way he speaks in sound-bites.

And, of course, the public loves a politician who's just like themselves.

© David Haywood, 2008.