The most recent Economist has an interesting, thought-provoking piece about the decline of centre-left parties across Europe in recent years. It’s well worth a read.

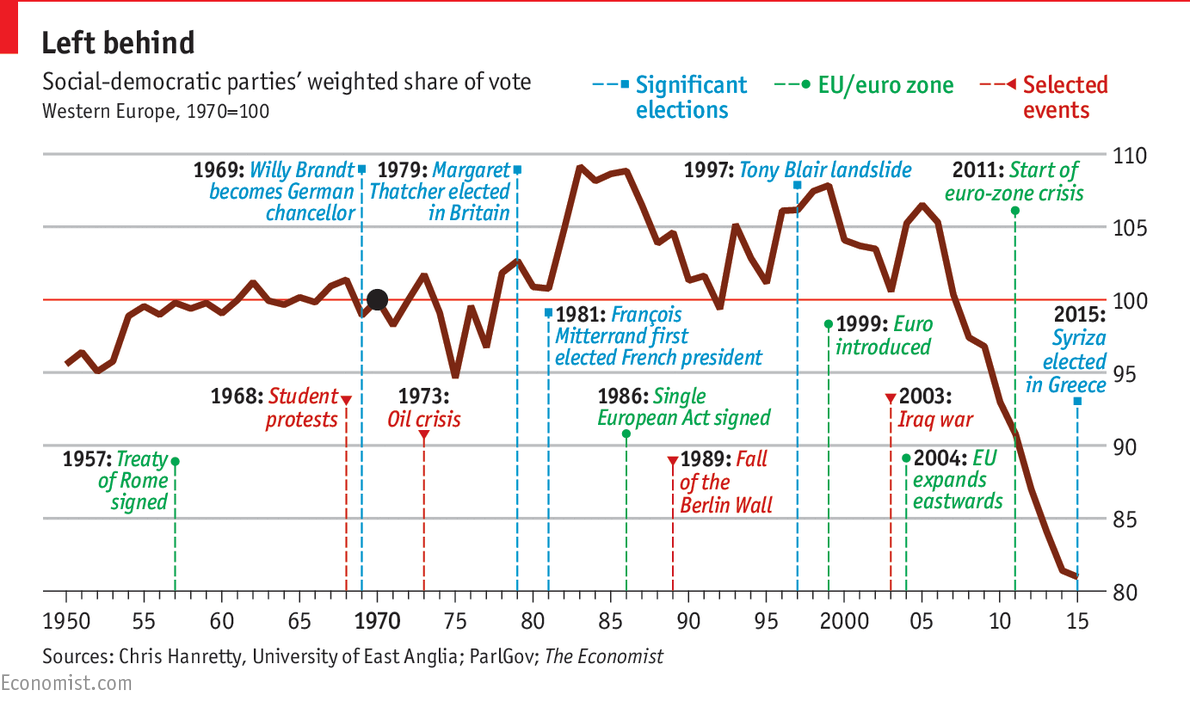

The headline figure is that social democratic parties, which were the dominant force in European politics as little as ten years ago, have now sunk to their lowest collective support for almost seventy years. The Economist’s graphic, reproduced here, illustrates the changes well, despite a little Y-axis chart crime:

Interestingly, the two recent periods of social democratic dominance in Europe coincide pretty nicely with the last two period of Labour government in New Zealand. It seems social democratic fortunes in New Zealand are mirroring those in Europe, even if the centre-left’s forces in Australia and North America are on a slightly different clock.

So, what’s gone wrong? The Economist thinks there are four things at play:

- Flagship social democratic policies like miminum wages, progressive taxes, and universal social entitlements are now supported across the spectrum. In short – the left’s won those battles.

- Rich country economies have changed towards more transient work in increasingly service-based roles, moving people’s economic needs away from traditional social democratic priorities.

- People around the industrialised world are more supportive of “strident” political candidates, such as Trump, Sanders, extreme anti-immigrant parties in Europe, and so on. With few exceptions, social democratic leaders aren’t cut from that cloth.

- The growth of self-identity as various forms of “middle class” has reduced affinity with traditionally social democratic notions like “working class,” which in turn affects public affinity with the traditional social democratic project.

I agree those four are all important considerations. I’ve talked about the victim-of-its-own-success factor before. If we have to endure a period of opposition in New Zealand, I’d much rather lose to a party that tries to ape Labour policy at so many turns than lose to a Ruth Richardson-style slash and burn administration.

That’s why as a progressive I’m quietly pleased when I see a National government reduced to crowing over its protection of working for families, increases to the minimum wage and benefits, increases to paid parental leave, and investment approach to social welfare, which is cited by Bill English as specifically designed to mollify lefties. To be clear, I'm pleased about the "targeting the most vulnerable" aspect of the investment approach, and much less pleased by the "increasing private provision" aspect.

Even though the progress is much slower than I’d prefer, it’s good to see progressive change happening even when the progressives are out of power.

I’d add a fifth factor for us to remember, too: Tough financial times are, in general, more likely to lead to conservative government. In good economic times, the left tends to do better. That, if I recall right, was a finding of Doug Hibbs in “The Political Economy of Industrial Democracies,” his seminal book on comparative political economy. The GFC of 2007-8 certainly counts as a suddenly-imposed tough economic time, and I think the fact that event happened at the same time as the centre-left started its deep European slide is no coincidence.

Of course the big question for progressives here is less “where did it come from,” and more “how do we fix it?”

On this score, the article is helpful because the continent-wide nature of the problem suggests that social democrats’ woes in any particular country are likely due to large-scale policy factors as well as particular personalities. Our media likes to heap praise on John Key and derision of the various Labour leaders. Sometimes that will be justified, but the trends indicate there are bigger forces at work, too.

That’s where the large-scale rethinking program in New Zealand Labour may have promise. New Zealand Labour is taking the needs of the new middle class seriously. Instead of asking “how can we make the new situation fit our old strictures” it's asking “how can we change our policies to fit the new group’s needs.” That’s the mindset that lead to Labour’s Future of Work Commission, and that the party is starting to apply in other areas, too.

Long may that bold thinking continue.

The social democratic movement is far from dead, of course, as the success of Obama and Trudeau shows. The big challenge for progressives here and elsewhere is to parse out which bits of the Obama and Trudeau recipies for success are specific to their country and to their particular opponents, and which parts travel well to other places.