It was a while before we noticed that there was something not quite right with our daughter. In our defence, it was pretty clear after her birth that there was something not quite right with me.

My midwife expressed her concerns about my seeming tired. I pointed out that I had a newborn and an eighteen month old. Surely tiredness was to be expected. She took my blood pressure. It was 60 over 40. I conceded that she might have a point, given I'd never heard those numbers without somebody yelling "she's crashing! 10ccs of technobabble, stat!".

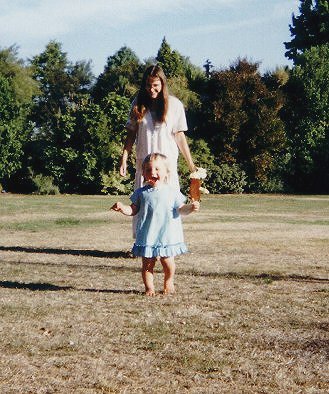

In all the trooping from specialist to specialist and explaining that it probably wasn't depression elevating my white blood cell count, any worries about our little girl could be easily pushed into the background. In comparison with her older brother, she was a breeze to look after: a sturdy, cheerful, pretty little girl with just a slight tendency to vanish every time you turned your back.

Butter actually does melt. We checked.

Then during our daughter’s standard two year check, our GP asked if we had any concerns. I looked at the top of my girl's head and said, "I don't think she can hear." I don't think I'd even thought that thought all the way to the end before I said it out loud. We weren't too concerned that she wasn't talking, because her brother had been slow to talk as well. He was one of those kids who went from not speaking at all to 'kill the succubus' without anything in between.

That was April. Over the next few months we discovered just how well the sturdy, pretty, incredibly cunning little 'princess' could fake an audiology test. You might think you weren't patterning, but she didn’t need to hear the sound to know when you were going to light up the drumming bunny. Twice we were assured that she was fine. I argued. Finally we were told the only remaining option was to put her through an auditory brainstem response test. This would mean anaesthetising her, with all the small degree of risk that attended. I told them to bring it on.

She loved the Children's Ward and its fulsome supply of Fisher-Price ride-in cars. I had to pin her to the bed after she had the anaesthetic, because she was aggressively convinced she was still okay to drive.

They told us the results before she woke up again, standing in a little room upstairs. There was a point at which the doctor's voice receded, becoming inaudible under a white sea of shock. He was telling us quite important things, but no matter how hard I tried I couldn't hear a word he said. I'd been right. My daughter had a severe to profound hearing impairment.

It took three more months to get her fitted with hearing aids and enrolled at van Asch. I can still vividly remember the first time we put those aids on her. She sat on her little plastic chair watching Teletubbies with her brother, fairly incurious as to why we were shoving things in her ears. And then we turned them on.

She went preternaturally still. You could see the desperate panic in her face as her brain scrambled to deal with this strange new input. She was only supposed to have the aids in for an hour or so at a time so she could adjust. She wouldn't let us take them out. She still doesn't like to take her aids out, even when she's going to sleep.

I was asked to decide whether Rhiana would be taught all in Sign, or all verbal. Making a decision of that magnitude for somebody else when I had no idea what their experience was like and couldn't ask them what they wanted was crushing. I've never stopped second-guessing it.

That was the beginning of a long, fraught journey for our family. We fought with teachers who didn’t want to use the microphone for her FM system. We fought a long and ultimately unsuccessful battle to retain her itinerant hours. We fought to get IEP meetings scheduled, and for ENT and audiology appointments. Everything that should have been hers by right, we had to fight for.

We know how lucky we are. We happen to live in the same city as one of New Zealand’s two deaf schools. Our daughter is extremely bright, so it's more a matter of exercising her full potential than struggling to stop her falling behind. At five she was drawing pictures of hills shaded to show how the sun was hitting them. At eleven, she's completely bloody-minded and her new haircut and general style of dress make her look like Starbuck. The new one, not the old one.

This has made me much more at peace with the word 'handicapped'. She was naturally so pretty and clever and talented that she's been given an extra load to carry, just to make it fair on everyone else.